Nuclear Advocates are Living in the Dark if They Think Rural America is Going to Embrace Microreactors

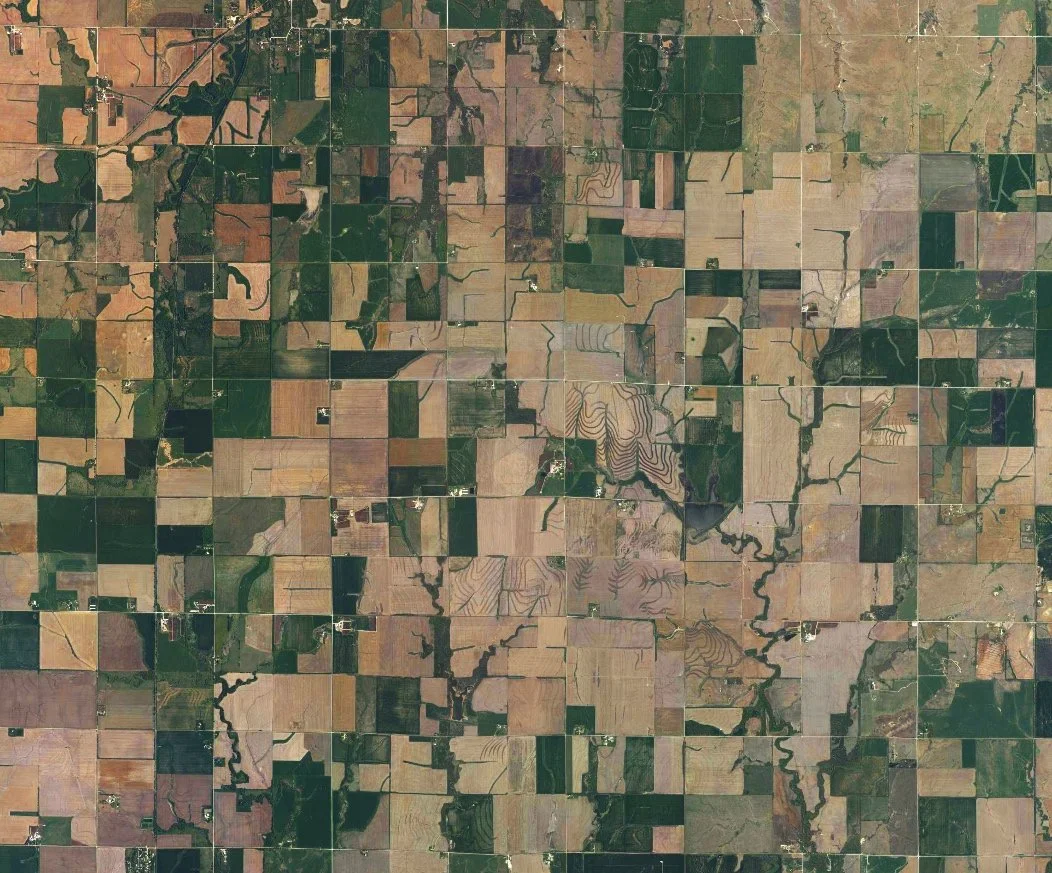

/As attorneys working with livestock producers, farmers, and rural landowners, we often have a front row seat to see the issues arising from land use in rural areas. The past few years we have seen dramatic changes to the rural landscape with addition of renewable energy projects. Wind farms, solar farms, anaerobic digesters that produce biogas, and carbon sequestration projects have added energy production to the many commodities that the agricultural landscape is already producing. These projects have also been good at generating local opposition. Now we hear nuclear microreactors will be the next big energy boom. How will rural America respond to more nuclear reactors?

First, what are nuclear microreactors? Nuclear microreactors are small reactors that generate less than 50 megawatts of electric power. By comparison, a conventional nuclear reactor can produce 1000 megawatts. The Department of Energy defines microreactors as having three characteristics:

Factory fabricated: All components of a microreactor are fully assembled in a factory and shipped to their installation location.

Transportable: Small unit designs make microreactors transportable by truck, ship, railcar or even airplane.

Self-adjusting: Microreactors are simple self-adjusting designs that do not require many specialized operators. They also have passive safety systems that prevent overheating or meltdown.

Second, what are the development challenges for microreactors? Microreactors are still a technology under development. Although smaller reactors are used on large warships and submarines, according to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), there are significant challenges in the road to commercial development. Microreactors use a fuel a described as high-assay, low-enriched uranium, or HALEU, which is currently unavailable in the commercial U.S. market. The GAO also states that the cooling and heat transfer technologies require further development. The compact size poses security risks, making the fuel an easier target for theft than at a well-secured, large conventional nuclear plant. And there are global security concerns, as widespread adoption of microreactors in the US could make nuclear technology more accessible and proliferate the technology to countries that pose a security threat.

Finally, how will rural America respond to microreactors if the technology becomes feasible? As attorneys working with rural landowners, we have witnessed the arrival of various modern technologies to rural landscape—wind turbines, solar farms, biogas digesters, battery energy storage systems (BESS), data centers, and deep-well carbon pore storage. Although the response in communities often begins as positive, welcoming the new jobs and tax base increases, attitudes often swing to negative, creating divisive local politics. Planning and zoning officials may then scramble to appease the pro- and anti-[Insert new technology here] factions. I will leave it to the sociologists to explain why people react so negatively to new developments in their neighborhoods. My theory is that the most vocal critics often have little to gain financially from new land use developments, so they oppose replacement of the cornfield with anything new. More cynical observers might describe this phenomenon as NIMBY (not in my backyard) or arising from CAVE people (citizens against virtually everything).

Considering this trend, micronuclear reactors will be even more controversial than the current suite of renewable energy projects. Even if the nuclear technology can be made commercially and economically viable, where are we going put these small nuclear reactors? If someone does not want a solar farm next to their home, they are certainly not going to embrace a nuclear reactor installed next door to power that new data center.

Personally, I think microreactor technology holds a lot of promise. Nuclear energy is a clean, low carbon based form of power. However, without some understanding of the local zoning challenges that accompany permitting of new technologies, we are kidding ourselves to think that America is ready for microreactors in the cornfield.